Smit Vasaiwala, MD is a board-certified electrophysiologist and cardiologist at Loyola Medicine who has a clinical interest in atrial fibrillation (AFib) and complex arrhythmia (heart rhythm) disorders.

Dr. Vasaiwala answers common questions about AFib to help patients better understand this condition.

How can I tell if I have atrial fibrillation?

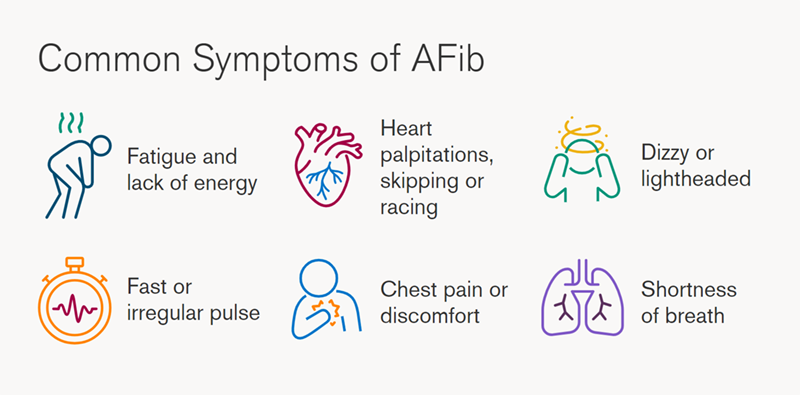

Atrial fibrillation, or AFib for short, is a fast heart rhythm that originates in the top chambers of the heart. AFib may cause no symptoms, but one early sign is an elevated pulse rate, and the most common symptom is tiredness.

Patients also may have heart palpitations, chest pain, shortness of breath or a skipping sensation in the chest.

The best way to know if you have atrial fibrillation is to see your doctor for regular checkups. While taking your pulse or listening to your heart, your doctor may notice either an irregular pulse or heartbeat.

A test called an electrocardiogram (ECG) is used to decide whether atrial fibrillation is causing the irregular pulse or heartbeat, which can have other causes.

How likely am I to have atrial fibrillation and not know it?

Most patients who have AFib will have symptoms, but it is not uncommon to have asymptomatic AFib, meaning there are no symptoms.

It is important to know that, whether you have symptoms or not, AFib raises your risk of having a stroke. Therefore, early recognition and treatment are important.

If my heart flutters occasionally, does that mean I have atrial fibrillation?

Not necessarily. There are other types of heart rhythm abnormalities that can cause the heart to feel as if it is fluttering or skipping. Some patients have skipped beats or extra beats that happen in succession.

Atrial fibrillation is more of a disorganized rhythm, and it raises a patient’s risk of stroke, while some other heart rhythm disorders do not.

Can atrial fibrillation be inherited?

There are patients who have hereditary AFib, although this is not typical. Patients with hereditary AFib tend to have a strong family history of AFib and show signs of the condition at a much younger age.

Are people usually born with atrial fibrillation?

No. It usually develops in the teens to 20s, if the cause is hereditary, and later in life, if it is due to other risk factors.

What contributes to atrial fibrillation?

There are several identified risk factors for AFib. Obesity, uncontrolled high blood pressure, diabetes, sleep apnea, thyroid abnormalities and excessive use of alcohol are some of them.

Although lack of exercise is not directly linked to the development of AFib, it can contribute to some of the risk factors.

Can atrial fibrillation be prevented?

Although there is no definite way to prevent atrial fibrillation, the risk can be lowered with proper control of blood pressure, diabetes and sleep apnea, and by losing weight, exercising, lowering stress and avoiding high-risk behaviors, such as excessive alcohol use.

What health problems can atrial fibrillation cause?

AFib is associated with risk of stroke. The risk is not the same for every patient and can be calculated based on one’s risk factors.

Older adults and women are at higher risk of stroke from AFib, as are people who have these conditions:

- Blocked arteries

- Congestive heart failure

- Diabetes

- High blood pressure

- Previous stroke

- Previous heart attack

What treatments are available for atrial fibrillation?

There are three key areas of treatment for atrial fibrillation (AFib):

- Stroke prevention: This is the most important. Depending on the number of risk factors you have, your doctor may recommend you take a blood thinner.

- Heart rate control: Because atrial fibrillation can cause your heart to race, your doctor may put you on a medicine to control your pulse rate. These medicines slow the impulses passing the AV node (the “electrical bridge” between the top and lower chambers of the heart), thereby slowing your pulse rate. This can alleviate some of the stress that AFib puts on your heart.

- Rhythm control: This is where a heart rhythm specialist comes into play. He or she may be able to keep your rhythm normal in multiple ways:

- Anti-arrhythmic drug therapy uses specialized medicines that work on the top chambers of the heart (atria) to keep the heart in rhythm.

- Cardioversion is a non-invasive procedure that involves shocking the heart back into the normal rhythm, almost like jump-starting an engine. Although the cardioversion is likely to be successful, you probably will need some medication to keep the rhythm normal. If not, your heart is at risk of going back into atrial fibrillation.

- Catheter ablation is a specialized procedure designed to reduce the burden of atrial fibrillation. The electrophysiologist (a cardiologist who specializes in treating rhythm abnormalities) places a catheter in the heart and ablates (electrically disconnects) specific areas in the heart where atrial fibrillation comes from. It is best to discuss the risks and benefits of this ablation procedure with your electrophysiologist.

- Pacemaker and ablation is the last resort therapy for atrial fibrillation. If medicine, catheter ablation and all other attempts at restoring normal rhythm have failed, and if your doctor is having trouble controlling your pulse rate, an “ablate and pace” strategy can help.

This involves cauterizing (ablating) the AV node (the electrical bridge connecting the top and lower chamber of the heart).

This will stop all electrical impulses from reaching the lower chambers of the heart. However, you can’t stop there; the heart requires electrical impulses to beat, so a pacemaker is needed. The pacemaker wire will be inserted and will stimulate the lower chambers of the heart to beat and will control the pulse rate.

- Anti-arrhythmic drug therapy uses specialized medicines that work on the top chambers of the heart (atria) to keep the heart in rhythm.

Can atrial fibrillation be cured?

No, atrial fibrillation (AFib) cannot be cured but can be controlled much like other illnesses such as diabetes or high blood pressure. Unless there is a clearly identified and reversible cause that is treated, there is always the risk of redeveloping atrial fibrillation. Therefore, ablation procedure is not a reason to stop blood thinners in patients who are at risk for stroke.

Smit Vasaiwala, MD, is a cardiologist at Loyola Medicine. His clinical interests include ablation catheter application for complex arrhythmias, ablation of atrial fibrillation, ablation of ventricular tachycardia, ablations for arrhythmias, arrhythmias, biventricular pacing, defibrillator devices, electrophysiology, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, radiofrequency ablation of cardiac arrhythmias and ventricular tachycardia.

Dr. Vasaiwala earned his medical degree at Loyola University Chicago's Stritch School of Medicine. He completed a residency in general internal medicine at University of Michigan Medical Center and two fellowships in cardiology and electrophysiology at Loyola University Medical Center.

Book an appointment today to see Dr. Vasaiwala or another Loyola specialist by self-scheduling an in-person or virtual appointment using myLoyola.