By Joseph Serrone, MD, Neurology & Neurosurgery

A brain aneurysm is simply a balloon-like outpouching of a blood vessel within the brain.

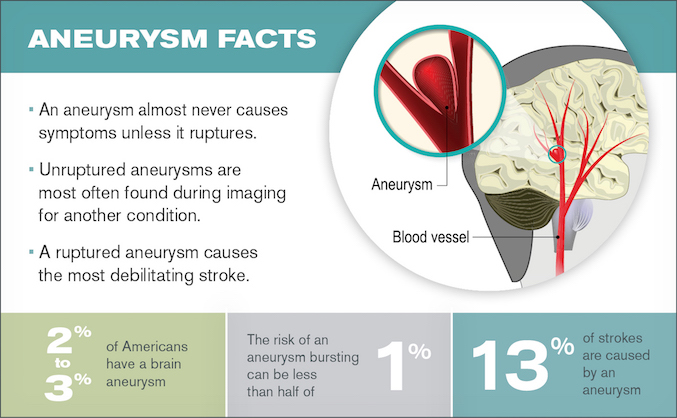

They are present in about 2 to 3% of the population and very commonly do not cause any symptoms in patients who harbor them.

Why then would you or a doctor be concerned about a brain aneurysm?

The concern arises because aneurysms have the potential to rupture, or burst open, and cause bleeding around the base of the brain. This condition is called subarachnoid hemorrhage and represents the most disabling type of stroke.

Patients experiencing a ruptured aneurysm require emergency evaluation at a stroke center to treat the aneurysm and be monitored in a critical care setting for 10 to 14 days after treatment.

Taking care of critically ill patients who have suffered a ruptured aneurysm is a significant portion of a neurosurgeon’s work.

Even more commonly, doctors evaluate patients who have an aneurysm that hasn’t ruptured. These aneurysms nearly always are discovered accidentally on an MRI that was taken to evaluate a headache or other symptoms.

Once an aneurysm is found, it requires a careful evaluation by a specialist who understands the risk an aneurysm could pose to the patient. Medical studies show the risk of a brain aneurysm rupturing is quite low.

In some cases, this risk can be less than half a percent per year and most brain aneurysms fall into this low-risk category. In these cases, neurosurgeons do not recommend treatment given the low risk to the patient.

However, all aneurysms are followed with brain imaging studies over several years to ensure they are not growing.

Treatment is considered if the brain aneurysm is at increased risk of rupturing. The aneurysms that are at increased risk of rupturing are:

- Larger than 7 mm

- Located at the back of the brain

- Irregularly shaped

- Growing, based on a series of imaging studies

An aneurysm found in someone who has had a ruptured aneurysm before or has a family history of brain aneurysms has a greater risk of a rupture occurring.

The job of neurosurgeons and other specialists who manage aneurysms is to determine which ones pose a high enough risk to warrant treatment and which ones should be left alone.

The goal of treatment is to prevent blood from entering the aneurysm. This can be accomplished by either a surgical procedure or an endovascular procedure.

The surgical procedure requires an operation in which a neurosurgeon makes a small opening in the skull and places a clip at the base of the aneurysm. This method has been used to treat aneurysms for over 50 years and remains the most durable method to permanently block the aneurysm. Patients typically spend three days in the hospital after surgery and are able to resume normal activities in two to three weeks.

The endovascular method of treatment approaches the aneurysm from inside the blood vessel, as opposed to surgery, which approaches the aneurysm from outside of the vessel. Endovascular treatment starts by accessing the femoral artery in the groin, and catheters are then navigated to the brain and placed inside the aneurysm. With a catheter inside the aneurysm, metal coils made of platinum are packed into the aneurysm, which prevents blood from entering the aneurysm and thus protect it from rupturing.

This form of treatment has been used for about 25 years and represents a less invasive way to treat the aneurysm. Patients typically spend one day in the hospital and return to normal activities within a few days.

Although endovascular treatment is less invasive and offers a quicker recovery, it is less durable. About 15% of aneurysms need to be treated again within two years.

There are many nuances that doctors contemplate before choosing whether to recommend surgery or endovascular treatment.

Our approach to evaluating aneurysms at Loyola Medicine is to bring together specialists from several medical disciplines, including neurosurgery, radiology, neurology and critical care, to have an open discussion of aneurysm cases. Such clinics allow doctors to draw from decades of experience and knowledge in making a sound recommendation to our patient

Now you have a foundation for understanding a complex condition that we take pride in treating.

Joseph Serrone, MD is a neurosurgeon at Loyola Medicine. His clinical interests include acoustic tumors, aneurysms, brain hemorrhage (bleeding), brain tumors, carotid artery surgery, carotid stenosis, complex cranial base tumors, endovascular therapy, intracranial occlusive disease, meningiomas, spine surgery, stroke and vascular malformations.

Dr. Serrone completed medical school at University of Missouri, Kansas City School of Medicine and completed a residency in neurological surgery at the University of Cincinnati along with fellowships in endovascular neurology and cerebrovascular & skull base surgery at the University of Cincinnati and Helsinki University Central Hospital, Finland, respectively.

Book an appointment today to see Dr. Serrone or another Loyola specialist by self-scheduling an in-person or virtual appointment using myLoyola.